Thursday, December 17, 2009

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

Final Exam

Monday, December 14, 2009

In Defense of Ads

Sunday, December 13, 2009

12/14 Class Canceled

The final exam will still be Friday, December 18th, and we'll still be reviewing for it on Wednesday.

As Usual, The Onion Nails It

"The new device is an improvement over the old device, making it more attractive for purchase by all Americans," said Thomas Wakefield, a spokesperson for the large conglomerate that manufactures the new device. "The old device is no longer sufficient. Consumers should no longer have any use or longing for the old device." (more...)

Saturday, December 12, 2009

I Approve This Dishonesty

Friday, December 11, 2009

After a Word from Our Sponsors...

- The first is about the underlying intellectual dishonesty in even the most honest of ad campaigns.

- By the way, if you're into advertising, that entire blog is great. I'm a bit biased, though, since I used to work with the guy who writes it.

- Here's a radio interview with the director of FactCheck.org, a great website devoted to debunking claims in political ads.

- I also used to work with the guy who interviewed FactCheck's director. Yup, I'm a pretty big deal.

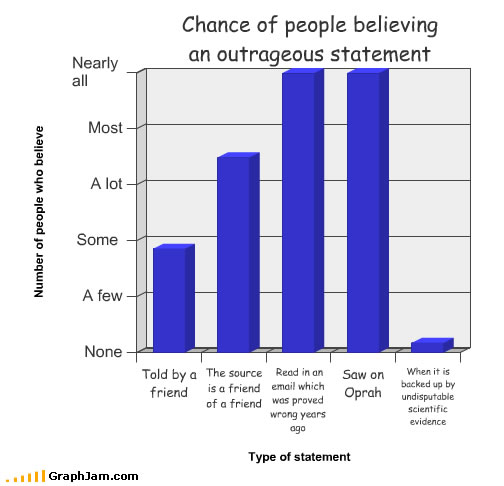

- I wish those fact checking websites made a difference. Actually, I just wish they didn't hurt their own cause. Silly humans and your naturally biased minds!

Monday, December 7, 2009

Homework #3

- First, very briefly explain the argument that the ad offers to sell its product.

- Then, list and explain the mistakes in reasoning that the ad commits.

- Then, list and explain the psychological ploys the ad uses (what psychological impediments does the ad try to exploit?).

- Attach (if it's from a newspaper) or briefly explain the ad.

Sunday, December 6, 2009

Wooden-Headed

Getting us to care is the real goal of this class. We should care about good evidence. We should care about evidence and arguments because they get us closer to the truth. When we judge an argument to be overall good, THE POWER OF LOGIC COMPELS US to believe the conclusion. If we are presented with decent evidence for some claim, but still stubbornly disagree with this claim, we are just being irrational. Worse, we're effectively saying that the truth doesn't matter to us.

This means we should be open-minded. We should be willing to challenge ourselves, and let new evidence change our current beliefs. We should be open to the possibility that we've currently gotten something wrong. This is how comedian Todd Glass puts it:

Here are the first two paragraphs of a great article I read last year on this:

Ironically, having extreme confidence in oneself is often a sign of ignorance. Remember, in many cases, such stubborn certainty is unwarranted.Last week, I jokingly asked a health club acquaintance whether he would change his mind about his choice for president if presented with sufficient facts that contradicted his present beliefs. He responded with utter confidence. "Absolutely not," he said. "No new facts will change my mind because I know that these facts are correct."

I was floored. In his brief rebuttal, he blindly demonstrated overconfidence in his own ideas and the inability to consider how new facts might alter a presently cherished opinion. Worse, he seemed unaware of how irrational his response might appear to others. It's clear, I thought, that carefully constructed arguments and presentation of irrefutable evidence will not change this man's mind.

Friday, December 4, 2009

Metacognition

There's a name for all the studying of our natural thinking styles we've been doing in class lately: metacognition. When we think about the ways we think, we can vastly improve our learning abilities. This is what the Owning Our Ignorance club is about.

There's a name for all the studying of our natural thinking styles we've been doing in class lately: metacognition. When we think about the ways we think, we can vastly improve our learning abilities. This is what the Owning Our Ignorance club is about.I think this is the most valuable concept we're learning all semester. So if you read any links, I hope it's these two:

Thursday, December 3, 2009

When Status Quo Isn't Good Enough

- If it already exists, we assume it's good.

- Our mind works like a computer that depends on cached responses to thoughtlessly complete common patterns.

- NYU psychologist John Jost does a lot of work on system justification theory: our tendency to unconsciously rationalize the status quo, especially unjust social institutions. Scarily, those of us oppressed by such institutions have a stronger tendency to justify their existence.

- Jost has a new book on this stuff. Here's a video dialogue about his research:

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

Let's All Nonconform Together

- On the influence of your in-groups and the formation of your identity: "If you want to set yourself apart from other people, you have to do things that are arbitrary, and believe things that are false." (from Paul Graham's "Lies We Tell Our Kids.")

- Here's a summary of two recent studies which suggest that partisan mindset stems from a feeling of moral superiority.

- Here's that poll showing the Republican-Democrat switcharoo regarding their opinion of Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke when the executive office changed parties.

- Our political loyalties also influence our view on the economy.

- Here's an article about a cool study on the relationship between risk and provincialism.

- Conformity hurts the advancement of science.

Tuesday, December 1, 2009

Wished Pots Never Boil

- If you're a fan of The Secret, you should beware that it's basic message is wishful thinking run amok.

- Teachers have biases, too: we're self-serving and play favorites.

- Why don't we give more aid to those in need? Psychological impediments are at least partly to blame.

- Why do we believe medical myths (like "vitamin C cures the common cold," or "you should drink 8 glasses of water a day")? Psychological impediments, of course!

Friday, November 27, 2009

Open-Minded

I like the definition of open-mindedness offered by this video: it is being open to new evidence. This brings with it a willingness to change your mind... but only if new evidence warrants such a change.

Changing your mind has gotten a bum rap lately: flip-flopping can kill a political career. But willingness to change your mind is an important intellectual virtue that is valued by scientists.

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

No, You're Not

You've probably noticed that one of my favorite blogs is Overcoming Bias. Their mission statement is sublimely anti-I'M-SPECIAL-ist:

This may sound insulting, but one of the goals of this class is getting us to recognize that we're not as smart as we think we are. All of us. You. Me! That one. You again. Me again!"How can we better believe what is true? While it is of course useful to seek and study relevant information, our minds are full of natural tendencies to bias our beliefs via overconfidence, wishful thinking, and so on. Worse, our minds seem to have a natural tendency to convince us that we are aware of and have adequately corrected for such biases, when we have done no such thing."

(By the way, this is especially true for the actually smart people among us: the more experienced you are, the more overconfident you're likely to become.)

So I hope you'll join the campaign to end I'M-SPECIAL-ism.

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

The Importance of Being Stochastic

Anyway, a few links:

- I brought up this article before, but I'll mention it again: most of us are pretty bad at statistical reasoning.

- That radio show I love recently devoted an entire episode to probability:

- Here's a review of a decent book (The Drunkard's Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives) on our tendency to misinterpret randomness as if it's an intentional pattern.

- This ability to see patterns where there are none may explain why so many of us believe in god (see section 5 in particular).

- What was that infinite monkey typewriter thing we were talking about in class?

- Statistics in sports is all the rage lately. It can justify counterintuitive decisions, like going for it instead of punting on 4th down... though don't expect the fans to buy that fancy math learnin'.

Monday, November 23, 2009

We Don't Know What Makes Us Happy

I'd like to teach a class devoted entirely to TED talks.

Saturday, November 21, 2009

Fight the Bias

Here are two other big, simple points I think are important:

- A

ctively seek out sources that you disagree with. We tend to surround ourselves with like-minded people and consume like-minded media. This hurts our chances of discovering that we've made a mistake. In effect, it puts up a wall of rationalization around our preexisting beliefs to protect them from any countervailing evidence.

ctively seek out sources that you disagree with. We tend to surround ourselves with like-minded people and consume like-minded media. This hurts our chances of discovering that we've made a mistake. In effect, it puts up a wall of rationalization around our preexisting beliefs to protect them from any countervailing evidence. - When we do check out our opponents, it tends to be the obviously fallacious straw men rather than sophisticated sources that could legitimately challenge our beliefs. But this is bad! We should focus on the best points in the arguments against what you believe. Our opponents' good points are worth more attention than their obviously bad points. Yet we sometimes naturally focus on their mistakes rather than the reasons that hurt our case the most.

Friday, November 20, 2009

Rationalizing Away from the Truth

- Recent moral psychology suggests that we simply rationalize our snap moral judgments. (Or worse: we actually undercut our snap judgments to defend whatever we want to do.)

- The great public radio show Radio Lab devoted an entire show to the psychology of our moral decision-making:

- Humans' judge-first, rationalize-later approach stems in part from the two competing decision-making styles inside our heads.

- For more on the dual aspects of our minds, I strongly recommend reading one of the best philosophy papers of 2008: "Alief and Belief" by Tamar Gendler.

- Here's a video dialogue between Gendler and her colleague (psychologist Paul Bloom) on her work:

Thursday, November 19, 2009

More to Forget

- Here's an overview on the way our memory is faulty by psychologist Gary Marcus. He's written a book called Kluge: The Haphazard Construction of the Human Mind.

- Even strong "flashbulb memories" like what you were doing on 9/11 are not very accurate.

- One leading expert on memory is psychologist Elizabeth Loftus. Here is a pair of articles that summarize her research on false memories, and here's a video of her presenting on it.

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

Filling in Memory

The preview cuts off at the bottom of page 80. Here's the rest from that section:

"...reading the words you saw. But in this case, your brain was tricked by the fact that the gist word--the key word, the essential word--was not actually on the list. When your brain rewove the tapestry of your experience, it mistakenly included a word that was implied by the gist but that had not actually appeared, just as volunteers in the previous study mistakenly included a stop sign that was implied by the question they had been asked but that had not actually appeared in the slides they saw.Too many words, Sean! Can't you just put up a video? You better make it funny, too!

"This experiment has ben done dozens of times with dozens of different word lists, and these studies have revealed two surprising findings. First, people do not vaguely recall seeing the gist word and they do not simply guess that they saw the gist word. Rather, they vividly remember seeing it and they feel completely confident that it appeared. Second, this phenomenon happens even when people are warned about it beforehand. Knowing that a researcher is trying to trick you into falsely recalling the appearance of a gist word does not stop that false recollection from happening."

Fine. Here's Dan Gilbert on The Colbert Report:

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

Direct Experience

Next, watch this:

Finally, here's an article on this issue. Still trust your direct experience?

Saturday, November 14, 2009

Ask Friends... Old Friends

- Often times, our friends know more about us than we do.

- While talking to your friends, you might want to ask more about them. It turns out that they're less like us than we might think.

- Also, consider listening to advice from older people. We're not as different from them as we think.

Friday, November 13, 2009

Thursday, November 12, 2009

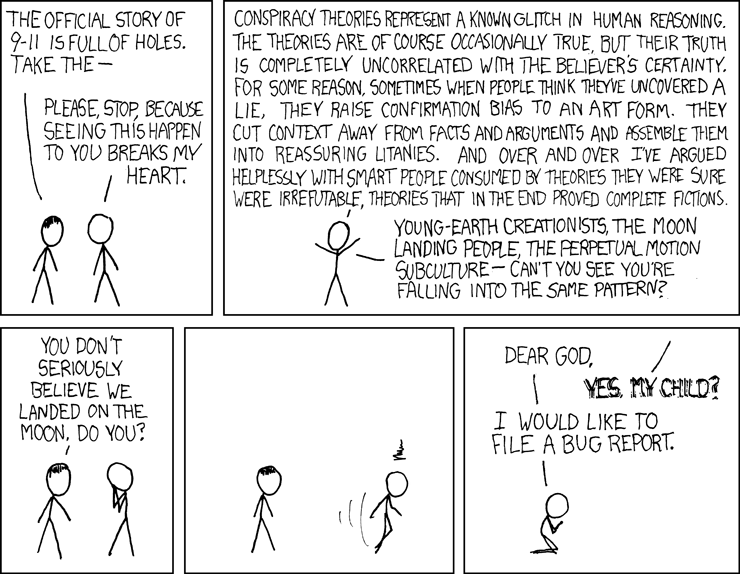

The Conspiracy Bug

While there are a handful of Web sites that seek to debunk the claims of Mr. Jones and others in the movement, most mainstream scientists, in fact, have not seen fit to engage them.And one more excerpt on reasons to be skeptical of conspiracy theories in general:

"There's nothing to debunk," says Zdenek P. Bazant, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northwestern University and the author of the first peer-reviewed paper on the World Trade Center collapses.

"It's a non-issue," says Sivaraj Shyam-Sunder, a lead investigator for the National Institute of Standards and Technology's study of the collapses.

Ross B. Corotis, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Colorado at Boulder and a member of the editorial board at the journal Structural Safety, says that most engineers are pretty settled on what happened at the World Trade Center. "There's not really disagreement as to what happened for 99 percent of the details," he says.

One of the most common intuitive problems people have with conspiracy theories is that they require positing such complicated webs of secret actions. If the twin towers fell in a carefully orchestrated demolition shortly after being hit by planes, who set the charges? Who did the planning? And how could hundreds, if not thousands of people complicit in the murder of their own countrymen keep quiet? Usually, Occam's razor intervenes.

Another common problem with conspiracy theories is that they tend to impute cartoonish motives to "them" — the elites who operate in the shadows. The end result often feels like a heavily plotted movie whose characters do not ring true.

Then there are other cognitive Do Not Enter signs: When history ceases to resemble a train of conflicts and ambiguities and becomes instead a series of disinformation campaigns, you sense that a basic self-correcting mechanism of thought has been disabled. A bridge is out, and paranoia yawns below.

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

Penguin Digestion Experts? You Bet!

- Adjustments of gastric pH, motility and temperature during long-term preservation of stomach contents in free-ranging incubating king penguins from a 2004 issue of Journal of Experimental Biology

- Feeding Behavior of Free-Ranging King Penguins (Aptenodytes Patagonicus) from a 1994 issue of Ecology

Perhaps my favorite, though, is the following:

- Pressures produced when penguins pooh—calculations on avian defaecation from a 2003 issue of Polar Biology

Monday, November 9, 2009

An Expert for Every Cause

Not all alleged experts are actual experts. Here's a method to tell which experts are phonies (this article was originally published in the Chronicle of Higher Education).

It's important to check whether the person making an appeal to authority really knows who the authority is. That's why we should beware of claims that begin with "Studies show..."

And here's a Saturday Night Live sketch in which Christopher Walken completely flunks the competence test.

Saturday, November 7, 2009

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Begging the Dinosaur

I couldn't resist giving you some stuff on begging the question. Here's my favorite video for Mims's logically delicious song "This is Why I'm Hot":

I couldn't resist giving you some stuff on begging the question. Here's my favorite video for Mims's logically delicious song "This is Why I'm Hot":

Sunday, November 1, 2009

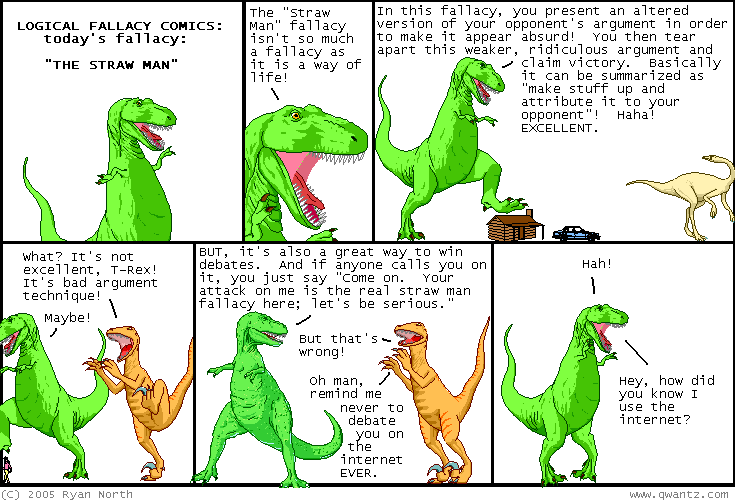

Let's Be Diplomatic: Straw Person

Here's some stuff on the straw man fallacy:

- Politicians love to distort their opponents' positions. Even Obama does it.

- Politicians aren't alone: we do it, too. Often we distort arguments for claims we disagree with without even realizing it. This is because we have trouble coming up with good reasons supporting a conclusion that we think is false, so we have a tendency to make up bad reasons and attribute them to our opponents.

- Hire your own professional straw man!

Wait, we weren't just speaking of red her--Oh. I see what you did there.

Clever.

Thursday, October 29, 2009

Paper Guideline

Worth: 5% of final grade

Length/Format: Papers must be typed, and must be between 300-600 words long. Provide a word count on the first page of the paper. (Most programs like Microsoft Word & WordPerfect have automatic word counts.)

Assignment:

1) Pick an article from a newspaper, magazine, or journal in which an author presents an argument for a particular position. I will also provide some links to potential articles at the course website. You are free to choose any article on any topic you want, but you must show Sean your article by Monday, Novemer 16th, for approval. The main requirement is that the author of the article must be presenting an argument. One place to look for such articles is the Opinion page of a newspaper. Here’s a short list of some other good sources online:

- The New Yorker

- Slate

- New York Review of Books

- London Review of Books

- Times Literary Supplement

- Boston Review

- Atlantic Monthly

- The New Republic

- The Weekly Standard

- The Nation

- Reason

- Dissent

- First Things

- Mother Jones

- National Journal

- The New Criterion

- Wilson Quarterly

- The Philosophers' Magazine

2) In the essay, first briefly explain the article’s argument in your own words. What is the position that the author is arguing for? What are the reasons the author offers as evidence for her or his conclusion? What type of argument does the author provide? In other words, provide a brief summary of the argument.

NOTE: This part of your paper shouldn’t be very long. I recommend making this about one paragraph of your paper.

3) In the essay, then evaluate the article’s argument. Overall, is this a good or a bad argument? Why or why not? Check each premise: is each premise true? Or is it false? Questionable? (Do research if you have to in order to determine whether the author’s claims are true.) Then check the structure of the argument. Do the premises provide enough rational support for the conclusion? If you are criticizing the article’s argument, be sure to consider potential responses that the author might offer, and explain why these responses don’t work. If you are defending the article’s argument, be sure to consider and respond to objections.

NOTE: This should be the main part of your paper. Focus most of your paper on evaluating the argument.

4) Attach a copy of the article to your paper when you hand it in. (Save trees! Print it on few pages!)

TIP: It’s easier to write this paper on an article with a BAD argument. Try finding a poorly-reasoned article!

TIP: It’s easier to write this paper on an article with a BAD argument. Try finding a poorly-reasoned article!

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

Possible Paper Articles

- Bad Stereotyping: race & gender = insufficient info

- The Idle Life is Worth Living: in praise of laziness

- In the Basement of the Ivory Tower: are some people just not meant for college?

- Who Would Make an Effective Teacher?: we're using the wrong predictors

- Study Says Social Conservatives Are Dumb: but that doesn't mean they're wrong

- The Financial Crisis Killed Libertarianism: if it wasn't dead to begin with

- How'd Economists Get It So Wrong?: Krugman says the least wrong was Keynes

- An Open Letter to Krugman: get to know your field

- Consider the Lobster: David Foster Wallace ponders animal ethics

- Genetically Engineered Pain Free Animals: would it be ethical to make 'em feel no pain?

- Is Worrying About the Ethics of Your Diet Elitist?: since you asked, no

- Loyalty is Overrated: adaptability & autonomy matter more

- FBI Profiling: it's a scam, like psychic cold reading

- Singer: How Much Should We Give?: just try to think up a more important topic

- Can Foreign Aid Work?: it has problems, but we should use it

- The Dark Art of Interrogation: Bowden says torture is necessary

- Opposing the Death Penalty: it's not about innocence

- You Don't Deserve Your Salary: no one does

- Against Free Speech: but it's free, so it must be good

- What pro-lifers miss in the stem-cell debate: love embryos? then hate fertility clinics

- Is Selling Organs Repugnant?: freakonomicists for a free-market for organs

- Why I Have No Future: Strawson's intuition that death's not bad

- Should I Become a Professional Philosopher?: hell 2 da naw

- Blackburn Defends Philosophy: it beats being employed

Friday, October 23, 2009

Midterm Reminder

- definitions of 'logic,' 'reasoning,' and 'argument'

- evaluating arguments

- types of arguments:

-deductive (aim for certainty, are valid/invalid and sound/unsound)

-inductive (generalizing from examples, depend on large, representative samples)

-args about cause/effect

-abductive (inferences to the best explanation) - the ten fallacies covered in class so far

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Homework #2

Tuesday, October 20, 2009

That's an Ad Hominem, Jerk

Here's some links on the ad hominem (personal attack) fallacy:

Here's some links on the ad hominem (personal attack) fallacy:- Sure, some critics of Obama are racist, but does that mean we can dismiss their arguments? As much as we might want to, logically, no we cannot!

- Some variants on the personal attack: tu quoque (hypocrite!) and guilt by association (she hangs around bad people!).

- I should note that tu quoque isn't always fallacious reasoning.

- "The ad hominem rejoinders—ready the ad hominem rejoinders!"

- Remember our rallying cry: "STUPID PEOPLE SOMETIMES SAY SMART THINGS."

Sunday, October 18, 2009

Take My Wife, As Amphiboly

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

Fallacies, Fallacies, Everywhere

Speaking of, my best friend the inter-net has some nice examples of the fallacy of equivocation. Here is one good one:

Saturday, October 10, 2009

Murder on the Abductive Express

(NOTE: Platt uses the word "inductive" in a more general way than we do in class, to refer to any non-deductive kind of reasoning.)

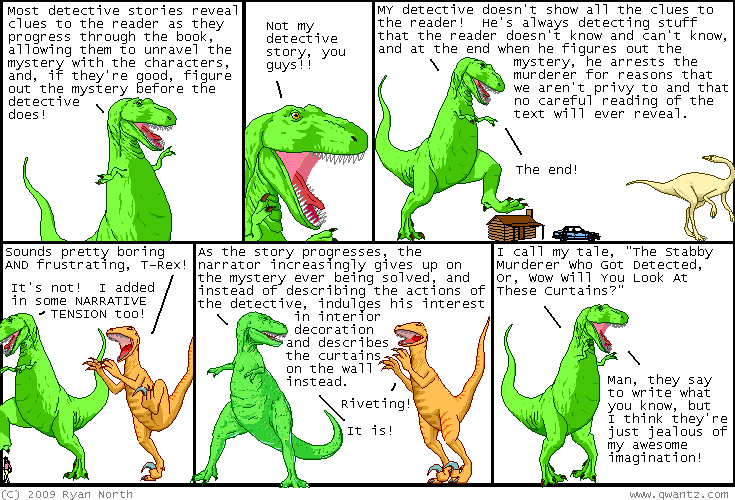

Also, in honor of abductive arguments, here's a dinosaur comic murder mystery.

Thursday, October 8, 2009

Learning From Mistaking

If you like stuff like this, you'll probably like the "Owning Our Ignorance" club.

“How experts learn, they really learn by looking at their mistakes. And this can be an unpleasant way to live, because who wants to get home after a long day’s work and think about all the stuff you messed up that day. And yet that tends to be a very effective way to learn. As Beckett said: ‘Fail. Fail better. Fail. Fail better.’ It’s that process of realizing that we all make mistakes. We all fail.

“I talk about it in terms of a variety of domains. I talk about it in terms of a backgammon player. After every match, even matches he wins, he goes back and looks at all the moves he did badly.

“I talk about a soap opera director who, after a day of shooting–a 16-hour day–he goes home and puts in the raw tape from that day and forces himself to make a list of thirty things he did wrong. Thirty mistakes so minor that no one else would notice them.

“Tom Brady: when Tom Brady watches game tape for hours every week, he’s not looking for the passes he did well. He’s looking for the passes he missed, for the open men he didn’t find.

“We need to think about how we think about learning and see mistakes as the inevitable component of learning. You can’t learn at a very fundamental level unless you get stuff wrong. And so not to fear our mistakes. Not to loathe them. Not to be so scared of making them. But to realize that we have to, in a sense, celebrate them. That they are an inevitable component of learning and you can’t learn without them.”

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

Group Presentations

- Accent & Division (10/12): Alisha, Ryan

- Ad Hominem & Appeal to Force (10/14): Ashley, Kristina

- Appeal to Pity & Popular Appeal (10/16): Kyle, Sam

- Appeal to Ignorance & Hasty Generalization (10/19): Dan, Johnny, Matt

- Straw Man & Red Herring (10/26): Christopher, Dominick

- Begging the Question & Loaded Question (10/28): Jonathan, William

- Appeal to Authority & False Dilemma (10/30): Amy, Elaine

- Slippery Slope & The Naturalistic Fallacy (11/02): Kathi, Lola

Friday, October 2, 2009

Causalicious

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

Learning From Experience

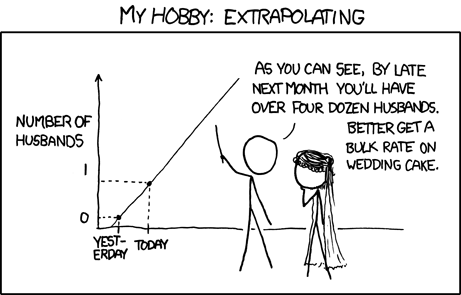

Next, a stick figure comic offers a pretty bad argument. Why is it bad? (Let us know in the comments!)

There's another stick-figure comic about scientists' efforts to get as big a sample size as they can to improve their arguments.

Finally, some more thoughtful links.

- What are the benefits and dangers of generalizations?

- What makes stereotyping illogical?

- Beware: we often make snap judgments before thinking through things. Then when we do think through things, we just wind up rationalizing our snap judgments.

Thursday, September 24, 2009

Quiz You Once, Shame on Me

The quiz is on what we have discussed in class from Chapters 6, 8, and 7 of the textbook. Specifically, here's what will be covered on the quiz:

- definitions of: logic, reasoning, argument, structure, sound, valid, deductive, inductive

- understanding arguments

- evaluating arguments

- deductive args (valid & sound)

- fancier deductive args

- inductive args

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Evaluating Deductive Args

1) All humpback whales are whales.

All whales are mammals.

All humpback whales are mammals.

P1- true

P2- true

structure- valid

overall - sound

Bush was either a great prez or the greatest prez.

Bush wasn’t the greatest prez.

Bush was a great prez.

P1- questionable ("great" is subjective)3) Some cats can speak German.

P2- questionable ("great" is subjective)

structure- valid (it's either A or B; it's not A; so it's B)

overall- unsound (bad premises)

Sean has a cat.

Sean's cat can speak German.

P1- false4) All knock-knock jokes are annoying.

P2- true! (I have two; there they are! ------------>)

structure- invalid (the 1st premise only says some can speak German; Sean's cat could be one of the ones that doesn't)

overall- unsound (bad structure)

Some knock-knock jokes are funny.

Some annoying things are funny.

P1- questionable ("annoying" is subjective)5) All whales are mammals.

P2- questionable ("funny" is subjective)

structure- valid (the premises establish that some knock-knock jokes are both annoying and funny; so some annoying things [those jokes] are funny)

overall - unsound (bad premises)

All whales live in the ocean.

All mammals live in the ocean.

P1- true6) Some dads have beards.

P2- true (if interpreted to mean "Whales are the sorts of creatures whose natural habitat is the ocean.") or false (if interpreted to mean "Each and every living whale lives in the ocean," since some whales, like Shamu, live in SeaWorld or other zoos)

structure- invalid (we don't know much about the relationship between mammals and creatures that living in the ocean just from the fact that whales belong to each of those groups)

overall- unsound (bad structure)

All bearded people are mean.

Some dads are mean.

P1- true7) This class is boring.

P2- questionable ("mean" is subjective)

structure- valid (if all the people with beards were mean, then the dads with beards would be mean, so some dads would be mean)

overall- unsound (bad 2nd premise)

All boring things are taught by Sean

This class is taught by Sean.

P1-questionable ("boring" is subjective)8) All students in this room are mammals.

P2- false (nearly everyone would agree that there are some boring things not associated with your teacher Sean)

structure- valid

overall- unsound (bad premises)

All humans are mammals.

All students in this room are humans.

P1- true

P2- true

structure- invalid (it's the same structure as argument #10 below; the premises only tell us that students and humans both belong to the mammals group; we don't know enough about the relationship between students and humans from this; for instance, what if a dog were a student in our class?)

overall- unsound (bad structure)

9) All hornets are wasps.

9) All hornets are wasps.All wasps are insects.

All insects are scary.

All hornets are scary.

P1- true!10) All women are mammals.

P2- true

P3- questionable ("scary" is subjective)

structure- valid (same structure as in argument #1, just with an extra premise)

overall- unsound (bad 3rd premise)

All men are mammals.

All men are women.

P1- true11) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- true

structure- invalid (just because men and women belong to the same group doesn't mean that men are women; same bad structure as in arg #8)

overall- unsound (bad structure)

Sean is singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

P1- questionable (since you haven't heard me sing, you don't know whether it's true or false)12) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- false (I'm not singing now!)

structure- valid

overall- unsound (bad premises)

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)13) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- true

structure- invalid (from premise 1, we only know what happens when Sean is singing, not when he isn't singing; students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- unsound (bad 1st premise and structure)

Students aren't cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)14) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- true

structure- valid

overall- unsound (bad 1st premise)

Students are cringing right now.

Sean is singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)

P2- false

structure- invalid (from premise 1, we only know that Sean singing is one way to guarantee that students cringe; just because they're cringing doesn't mean Sean's the one who caused it; again, students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- unsound (bad premises and structure)

Tuesday, September 22, 2009

Homework #1

The homework is due at the beginning of class on Friday, September 25th. It's worth 4% of your overall grade.

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

Structure

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises, if they were true, would provide good evidence for us to believe that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, they would convince you that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures guarantee that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Deductive Args (Valid)

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true for an argument to have a good structure. Notice we are only assuming truth, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows must be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.

All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, MUST the conclusion also be true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths guarantees a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Deductive Args (Invalid)

In an argument with a bad structure, you can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – they don’t naturally follow. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting whales take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

Club Meeting

We're having our first meeting of the school year Sunday night at the Barnes & Noble in Deptford. More info on the meeting and the club are available here.

If you're interested, come on out!

Sunday, September 6, 2009

Extra Credit: Tiffany's Argument

What part is the conclusion? Which parts are the premises? Be sure to give me your reasons why you got the answer you got. The extra credit is due at the beginning of class on Wednesday.

Wednesday, September 2, 2009

Email Subscription

A blog (short for “web log”) is a website that works like a journal – users write posts that are sorted by date based on when they were written. You can find important course information (like assignments, due dates, reading schedules, etc.) on the blog. I’ll also be updating the blog throughout the semester, posting interesting items related to the stuff we’re currently discussing in class. You don't have to visit the blog if you don't want to. It's just a helpful resource. I've used a blog for this course a lot, and it's seemed helpful. Hopefully it can benefit our course, too.

Since I’ll be updating the blog a lot throughout the semester, you should check it frequently. There are, however, some convenient ways to do this without simply going to the blog each day. The best way to do this is by getting an email subscription, so any new blog post I write automatically gets emailed to you. (You can also subscribe to the rss feed, if you know what that means.) To get an email subscription:

1. Go to http://ccclogic2009.blogspot.com.

2. At the main page, enter your email address at the top of the right column (under “EMAIL SUBSCRIPTION: Enter your Email”) and click the "Subscribe me!" button.

3. This will take you to a new page. Follow the directions under #2, where it says “To help stop spam, please type the text here that you see in the image below. Visually impaired or blind users should contact support by email.” Once you type the text, click the "Subscribe me!" button again.

4. You'll then get an email regarding the blog subscription. (Check your spam folder if you haven’t received an email after a day.) You have to confirm your registration. Do so by clicking on the "Click here to activate your account" link in the email you receive.

5. This will bring you to a page that says "Your subscription is confirmed!" Now you're subscribed.

If you are unsure whether you've subscribed, ask me (609-980-8367; slandis@camdencc.edu). I can check who's subscribed and who hasn't.